Conversations: 001 - Joe Lonsdale

On chess, history, interning at PayPal, starting Palantir, and why we should still be optimistic about America.

Serial entrepreneur, venture capitalist, and contrarian thinker, Joe Lonsdale has been a fixture in the Silicon Valley technology ecosystem ever since the early 2000’s, when he accepted an internship to work at a little-known startup called PayPal while studying at Stanford. Since then, Joe has gone on to help found multiple billion dollar plus businesses such as Palantir, Addepar, Epirus, Resilience Bio and OpenGov. On top of being a prolific builder, Joe has also seen great success as a venture capitalist, having invested in some of the world’s most transformative startups including Oculus, Oscar Health, Anduril, and Flexport.

Joe is one of my favorite people to talk to, as he not only has deep and extremely well informed perspectives around economics, philosophy, history, and company building, but he also holds a variety beliefs that are orthogonal to the Silicon Valley echo chamber which is always extremely refreshing.

If you enjoy this conversation as much as I did, please check out Joe’s podcast American Optimist, where he interviews a variety of idiosyncratic guests about life, liberty, and the pursuit of meaningful outcomes.

Praying for Exits (PFE): Your childhood was unique in the sense that you grew up both in the heart of Silicon Valley, as well as having a mother and father who pushed you from a very young age academically and physically. How much do you attribute your current standing to a lifelong proximity to Silicon Valley versus a strong work ethic that was instilled early? Which was more important?

Joe Lonsdale (JL): Growing up in the Bay and having early exposure to competition and excellence were definitely advantages for me.

One of the great things about Silicon Valley is that it was this place where anyone with the right talent and work ethic could show up without much knowledge of the place, work their tails off, and win. The greats came from all over, including from places that some of the California natives would never think to visit. Those people from the Midwest and elsewhere — Asia, Africa, EU, Middle East, Russia, etc — regularly outperformed and partnered to create extraordinary companies.

As SV was already attracting so much talent, and much of the talent was having children, I had a big advantage versus most places in the world to grow up. Some of my friends were interested in math and chess — the sort of friends who teach you fractions and programming at a young age — and I would likely not have learned to program at 10 years old in 1992 growing up elsewhere. Later, we had high school friends building liquid-Nitrogen rigs to cool overclocked Intel Pentium chips they got from their parent's work so that we could play real-time games with better responsiveness / graphics, and friends with older brothers during the Internet bubble creating companies that taught me some early lessons. Being in the culture there let you learn more quickly and was a distinct positive, especially if you were competitive and interested in math/CS/etc, with supportive parents.

Six years ago, I wrote a bit more about my upbringing in Silicon Valley — https://www.quora.com/How-was-Joe-Lonsdale-able-to-rise-so-quickly

I worry that because of the serious cost inflation in the past generation, some of that great meritocratic element of California in SV is suffering. It’s really expensive to show up in California with nothing — much more than 20 years ago — so there is probably some greater advantage to insiders, and an even greater advantage to those who have more wealth than I did growing up in the middle class, as it's now more expensive to come and compete. Another new issue with SV — you also have so much unprecedented wealth generated in SV relative to the world as a whole these last two decades that it not only made it expensive, but attracted a whole new culture of hangers-on who are not the competitive, substantive people; these are the bureaucrats and (with some exceptions, of course) the typical HR / marketing / lawyers / financial deal-makers and other infrastructure glomming onto the deep entrepreneurial and technical substance of SV. That stuff that gloms on is much more likely to get distracted with virtue-signaling and ideology and make a mess of things, even as the area gets more expensive; there are still amazing people in SV and great companies being built, but it has all these new challenges and barriers, too.

(PFE): In high school, you were a two-time California scholastic state chess champion and went on to donate a lot of your time to teaching chess in public schools. In what ways do you believe that chess imitates life? In what ways do you believe that a knowledge of chess improves life?

(JL): I actually won the CA state championship in 5th and 6th grade, so I won K-6 twice — and our school team won the national grade level championships a couple times, and the state as well. We were studying 30, 40 hours a week for several years to get to that point, so it definitely built discipline and focus. My younger brothers also each won the state championship once!

My father was a great coach... and probably, not too many other kids our age were putting in that kind of effort and discipline. Similarly, I was probably the only kid that age religiously doing push-ups and pull-ups. I broke a few 20 year-old records for breastroke on my swim team and got gold a few times for my age group for the sizable East Bay Swim League for 9-10 and 11-12 ages. I guess you could say I peaked early, ha... But I definitely learned that hard work and discipline was tied to winning. One time I took a week off for a family vacation at the height of competitive swim season, and relaxed that week... and never got back to my best times that summer: you have to be careful when you take your vacations.

How does chess imitate life? It's about the combination of talent and hard work... you need both. I knew people who must have had some of the highest IQs in the world, could run circles around us in global math competitions, but if they hadn't put in the time we could crush them in chess. Just like Emanuel Lasker, one of the world champions whose games we study, was friends with Albert Einstein and would play him and beat him consistently. In tournaments, you also have to really put in the work and focus and you get tired after a weekend of serious games. It's all on you if you mess up or not, and just like a lot of times when you are building something in a startup, the accountability and need to keep pushing is really clear.

Chess unifies abstract thinking, compound decision making, and competition in one venue. So of course, it’s very useful for life and business, and I’ve been lucky to work with a lot of my old chess teammates (not a coincidence at all). My chess master used to tell me, "Nearly every great man was a chess player... but few chess players were great men." Chess prepares your mind for other great strategic disciplines. But also, the lesson to me was that after several years, once I had done it a lot and learned a lot and won the state championship and our team had won nationals, I needed to switch and go deep on other things like computer science.

My team and I won the CA team championship in high school, but at that point it hadn't been a focus for a few years — I retired from the serious tens of hours a week of chess at age 13 to focus on CS, sports, etc. But I really enjoyed chess and my father was an amazing chess coach whose public elementary school team won the state championship consistently the next two decades after I attended, and I learned a lot about coaching and management from him, too.

(PFE): You have stated that you have a deep appreciation for learning about different periods of history, which is a largely uncommon trait amongst successful Silicon Valley founders. Where do you find the overlap between learning history and building technology companies?

(JL): I don't know if it's that uncommon. Elon definitely reads and studies history, and I got to know Peter Thiel debating economic history with him. History helps you build frameworks about how the world works, as well as how it could be working differently than it is now. To invest and build successfully you need to be able to think about how the world works, and what might come next. To lead successfully, or go to battle successfully, you need to study other leaders and other battles.

History is often tied to systems-thinking, and systems-thinking is critical for visionaries either in government or business. One of the great living constitutional scholars is Philip Bobbitt, and his book "Shield of Achilles" maps out the last thousand years and shows how five different forms of government came to the fore based on the current military technologies and ideal military structures — what do you need economically and societally to support so many well-armored and mounted knights, or to be able to get the masses of peasants to all fight for you with rifles, or etc. That last one, as an example — you couldn't very well have a totally unequal Prussian aristocratic-dominated society and expect the peasants to all be armed with rifles and charging into battle passionately on your behalf! The old structure they had might have worked back in a feudal armored-knights age, but with Napoleon coming at you with mass rifle charges, to adapt and not be conquered, the constitutional form of government that could persist changed. This might conceptually rhyme with different ways businesses and industries are likely to transform and adapt based on different systemic forces and new innovation we see and plan for today.

Talking about history is also an interesting leadership test, a way to learn about the world but also about people around us. Of course, it’s full of nuance and color — and for some reason, we have a modern allergy to taking earnest views on history. These days, there's this low-brow temptation in pop-culture to look at history and not take any opinion – or to be constantly negative, looking down on the past because it’s the past. There is so much wisdom in our civilization and other civilizations that has been gained over time, that we don't study properly today — as if we are totally unique and special and humans like us haven't been around for thousands of years. It's a huge unfair advantage to have access to this past wisdom and lessons, in life and business.

What do I think of right away when I say this? Sparing you my comments on wisdom [I've been reading a lot from India and also Jewish scholars lately], and jumping to lessons by historical analogy — Churchill confronting the decay and dysfunctional bureaucracy in the Royal Navy before WW1 and dealing with bureaucrats and saving the day by overhauling the sclerotic culture he encountered echoes a lot of what we saw and confronted with Palantir. Caesar outperforming based on how he communicated, but also based on having the very best engineers and the substantive building he did on campaign gave a fascinating perspective on leadership and engineering. Closer to home, understanding the business cycles of the 19th and 20th century are key — seeing what happened in the 1890's with the arguments around gold and silver and the yellow brick road, in 1920 in the US [not to mention Germany], as well as the 1930's, with multiple perspectives, as well as the 1970's, are useful even just as table stakes is key to creating mental models for what we might be dealing with macroeconomically and with financial policy with our government and inflation, and what's possible today.

The cycles of history are always necessarily oversimplified, but I think even those are useful. I always appreciated Bill Clinton's mentor Carroll Quigley — his "Evolution of Civilizations" in particular, about the seven stages of civilization, how mixing on the frontier and combining different ideas and wisdom from multiple traditions is often part of starting a new civilization (this reminds me of some companies we've created). Or his lessons for example about how a universal empire decays, how groups that were critical to scaling the civilization's success begin to become special interests and exist mostly for their own sake — in an industry or company, let alone a civilization — and how that causes decay until it's invaded and wiped out. There are so many other analogies — it would be useful today for more of us to consider how the "frontiers" prosper and often innovate and advance by being forced to react to reality or perish — that is, facing real accountability keeps them nimble and adaptive and functional — even as the core of the empire, buoyed by wealth and success, indulges in virtue-signaling and nonsense and becomes decadent.

There might not be much in Churchill or Gibbon to help you sell software or accomplish specific technical tasks, but if you can really engage with history and come out with your own thoughts on it, you’ll be a better thinker and leader. And you’ll realize that many of the novel human and organizational problems you encounter aren’t novel at all.

(PFE): You joined PayPal as an intern early on during your time at Stanford. Are there any specific stories you can recount from the PayPal days that would go on to define your life in a significant way?

(JL): Well, one major lesson was that one of the first things I had to work on there was a virtually impossible task of setting up this HR installation of PeopleSoft. I found out years later you were supposed to hire lots of consultants, that it is a virtually impossible task to do just using the docs they had at the time. But anyway, I was looking into it myself and it was set up terribly; I spent maybe a week and 100 hours and read these horrible documents up late at night and tried calling a few people and tried getting going on it, and I wasn't getting anything done. If you thought this story was "you are supposed to hire all these consultants and it's hard but I figured it out", nope, I was just completely failing and it all made no sense to me. So I was stuck and bored by it. And I decided this was stupid, it wasn't worth my time, I feel pretty important about who I was as this 19 year old kid, so I was going to quit and go work on something more interesting, and I told my father this.

He convinced me not to quit, and to stay and try to find other things to do. I ended up learning how Bloomberg worked and helping the Treasurer with some of his work trading bonds. He taught me a lot about that market and got me learning more about finance (which made a lot more sense to me than PeopleSoft installation instructions). And I ended up finding other things to do for some of their deeply technical people working on anti-fraud and helping build tools for that, too as they caught bad guys — PayPal was losing millions a month to fraud. The lessons from those two things helped propel me to accomplish a lot in both finance and with some of the ideas behind Palantir... so my father was right for me not to quit, even though I was right that the Peoplesoft stuff was horrible! [Ironically, we now have a place next door to a wonderful guy who happens to have been CEO of PeopleSoft sometime around then, but never told him about this.]

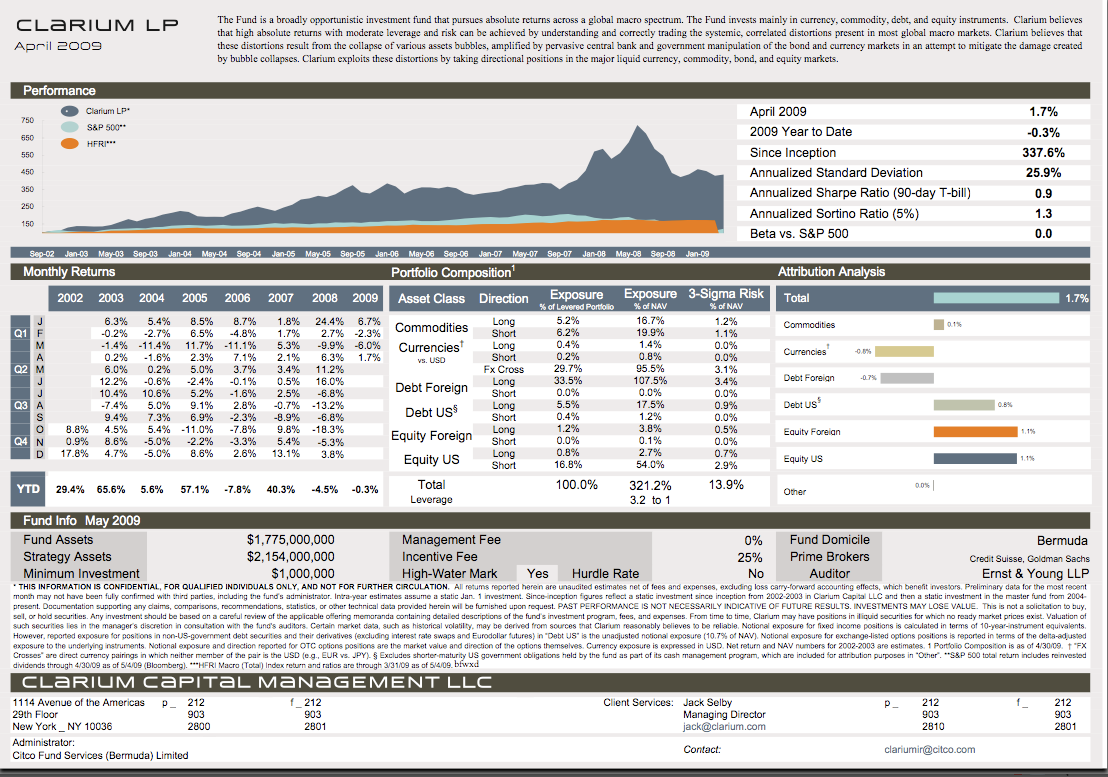

(PFE): After PayPal you would go on to work at Clarium Capital (Peter Thiel’s hedge fund). As many people know, Clarium was doing quite well in the early 2000’s and then came to an unfortunate end after a few directional bets did not pan out. How did this experience affect your entrepreneurship?

(JL): Well, there were a ton of very smart people at Clarium and a lot of very clever, very impressive trades that worked well over a number of years there. I learned a lot about global macro finance and the world, and the power of contrarian thinking, and the dangers of conspiratorial contrarian thinking in smart people, too. But I learned an even more important lesson.

So — I don't know if it came to an unfortunate end from directional bets not working out as you note. It is true we were up about 100% gross, 75% net by the late summer or early fall of 2008, betting against the banks and the unwinding of the mortgage market and housing bubble that year — we really got that right, just as we'd earlier made money on how GSE hedging in the mortgage market was distorting global fixed income. But from that point on in 2008, after hitting up 100% gross, we mistraded it badly... we tried to switch things up and go long, as the indicators showed things were oversold, and Peter believed the government would step in and bail everything out. He was ultimately absolutely right, but a few months too early! But, well, we went long in about 4-5 ways, and each of these ways had a 4% stop, and as the market crashed even more we were down ~20%. Then we did that two more times, and kept getting stopped out as the market crashed to unprecedented levels. We ended the year... I don't know, maybe up or down 4% total.

This really broke the culture there and created a lot of stress. There was lots of shouting and emotions - billions of dollars evaporating can do that. And because so much of the money was from fund-of-funds who got crushed and because we were so volatile — and maybe because we were a bit arrogant and not building long-term relationships with investors at that point — the fund went from say 8B to about 1B AUM after this. My account that year, I turned off as things were crashing as I didn't know what was going on, and ended up way up for the year still - but most of the compensation was tied to the main fund.

There were a lot of lessons, but probably the biggest lesson for me was how pride comes before the fall — we thought we were untouchable after a few years of crushing it with our models and insight and trading. Too important for leaders to talk to lots of LPs, too important for a lot of things, too confident. I saw it up close, and I was part of it and guilty of pride and over-confidence. As a 25 year old with a 60 million bonus or whatever it was coming my way if we had just stopped when we were up that much, it felt like we could do no wrong and that everybody should be taking notes from us! This is human nature; pride and arrogance comes easily with success.

I was really lucky to experience this early and get smacked around a bit by reality, and it made me far more paranoid, careful, and (I hesitate to say this, but it's a relative claim) humble. Speaking of history: we learn from the Greeks that the gods give men pride until it breaks them, and in some ways it’s unavoidable. I don’t know if it has to happen as a rule, and just because it happens to you once doesn’t mean you won’t make the mistake again, but it's useful to keep in mind.

(PFE): In 2004 you founded Palantir alongside Alex Karp, Peter Thiel, Nathan Gettings, and Stephen Cohen. What was the impetus at the time for the creation, and how aligned do you believe Palantir currently is to the original goal?

(JL): Yeah we started working on this in 2003, a very mission-driven company, and it's amazing to see how much the mission-driven energy and goals stayed with it even 19 years later. The impetus was, on one level, a better response to 9/11 – we saw our country under attack, and hated the idea of responding to it by wasting billions of dollars on broken and backward technology, with the FBI and others literally contracting and throwing out software solutions for hundreds of millions that didn't work, and in the meantime not tracking well enough who had access to what data / how data was used. As civil libertarians, this was very scary for us to see the government get this power unchecked and untracked.

At PayPal we got to know people from the Secret Service and FBI who were arresting the bad guys stealing money with various global mafia, and they would come to us after and ask for advice on how things worked with data and the Internet. We were interested in these areas and got to see a bit about their issues from that. And after PayPal and being in SV, we also knew about brand new technical possibilities coming out of the software revolution that the government wouldn’t be able to make use of without a new company to operationalize them, hiring the sort of talent that was unavailable out East at the time. DC was slow on new technology / didn't know how to judge a great technology culture vs a mediocre one (still mostly doesn't), and without us it was going to waste mountains of money failing to accomplish goals. We channeled the best technology cultures in order to fix that and bring critical defense infrastructure up to speed.

The GWOT is largely over, it’s been 20 years since 9/11, and we face different threats today. In that respect, Palantir’s work has changed a lot. We really did help stop hundreds of attacks, and help the US find thousands of terrorists much better than they would have, and changed the outcome there. But the bigger part of the mission that people sometimes miss about Palantir is that we created the most elite engineering culture in all of Silicon Valley for this patriotic purpose. That hasn’t changed. I brought in my roommate Stephen from Stanford and it wouldn't have worked without him and he is still there - he and I really led things early on with the product design and the push there, and Nathan had a lot more experience building an engineering team and being the full-time adult in the room. We have written elsewhere about how we spent so much time on vision and mission and hiring top talent. Thiel stopped us from making several key mistakes and provided the capital and impetus, and credibility without which it would have been impossible. Karp had a wisdom all of his own, and really grew as a CEO — I have written a lot more about this elsewhere. Karp has a great article they wrote in the WaPo in the last few weeks about Palantir's role in Ukraine - I'm really proud of everything they are still accomplishing.

When you bring some of the best engineers on the planet together for a critical mission, they can be one step ahead of any enemy – whether it’s decentralized terrorist groups, land armies, or even novel threats.

Here’s another Quora post about how Alex Karp became CEO: https://www.quora.com/How-did-Alex-Karp-get-chosen-as-Palantir-CEO

And here’s a post about why we built Palantir, released for the direct listing in 2020:

(PFE): In 2009, you left Palantir to found Addepar, a wealth management platform for RIA’s that now has an AUM of approximately $2.7 trillion. This was after your self-proclaimed ‘toughest year’ in 2008, when things came crashing down for you from both a financial and personal perspective. While not exactly analogous, many people believe that 2023 will be a year of difficulty. What advice would you give to people attempting to build in overwhelmingly difficult times?

(JL): Crisis as an opportunity is a bit of a cliche — but it's true that if you step forward as a leader and inspire talent to build alongside you with a solution during tough times, you can achieve things that might otherwise be impossible. Palantir was in many ways a response to 9/11; as founders we were working on it as a mission-driven company based on that, and I think a lot of extraordinary people were willing to help us who might not have been if they didn't recognize the challenges.

This dynamic plays a role in a lot of our other work, from important defense companies we are building now, including Epirus which is a unicorn we started that has perhaps the top EMP solution in the world, to Resilience Bio the multi-billion dollar advanced manufacturing company we started in early 2020 with Bob Nelson with help from many leaders across the pharma and biotech world who were more willing to step up and chat / get involved as part of working on a solution to a crisis. It was created in response to the early pandemic, as we got organized to see what we could build — we built a lot to create a new back-end for a lot of new advanced therapeutics, before we understood what would be needed for COVID — and it ended up playing a positive role there and in many other areas of cell therapy, gene therapy, mRNA, etc.

Similarly, Addepar was based on lessons from the messes coming out of the 2008 crisis, after we understood how much of finance was totally disconnected from the digital economy, which meant there was a ton of stuff that wasn't data-driven or that worked through insular networks (such as 'old boy clubs', and etc) vs what was possible. The core of finance is really the money / assets — people and institutions get to decide how they allocate it, and it's a huge mess to know what a large institution or family office owns, what liquidity they have, what trade-offs they are making and how it rolls up from different structures and trusts... and it was impossible at the time for any apps to talk to that information electronically to help with decisions or transactions or otherwise. Addepar crossed over $4 trillion in assets run on the platform [by tens of thousands of wealth advisors] in 2022 by the way.

A lot of people forget that most businesses take a decade or more to really reach maturity. Fifteen years is probably the right index value to think about. We probably didn’t have enough recessions or real tough times given ZIRP between 2008 and 2022, it may even have made people soft, or taught them that IPOs or SPACs would come in under five years. A tough macro environment like the present is actually a very good clarifying agent, and in addition to exposing some of the ideas that were overbought, it’s exposing that some people thought they were entitled to beat the market, and to get outsized returns in a very short period. I don't know if the recession we expect in 2023 is enough of a crisis to spur specific ideas like Palantir and Addepar and Resilience (although the Ukraine defense situation and other aspects of geopolitical defense challenges might be). I expect if we have more than a few rough years in a row economically, it might shift things more dramatically - not all in a good way, but there will certainly be very new challenges for us to face.

If you’re committed and the business has real technology that addresses a real gap in the world, the macro environment shouldn’t be reason for panic, and my advice is to find an area where you and people around you can be the very best and stay focused on your mission and executing on it, and keep trying to surround yourself with great talent in and around the company. And if there is a crisis and you know how you can build and be part of a solution, that's a great excuse to attract talent and allies and build something worthwhile.

(PFE): Formation 8, the precursor to your current Venture Capital fund, 8VC, allegedly recorded a net IRR of 95% back in the early 2010’s before abruptly disbanding shortly after raising Fund II. Would you have done anything differently here?

(JL): Well, early IRR's tend to be really high when you have early mark-ups and exits which we did with RelateIQ and Oculus and otherwise, and both Formation 8 1 and 2 are successful funds — despite the huge downturn in some of the public stocks these last couple years — and I'm proud of the work we did. I worked with some talented former partners, who happened to be Korean, and it was a great way to get started as my first time being a full-time venture investor — they each did deals I admire, and my partner's father from the LG family in Korea put up the initial 50M USD anchor that made it possible for me to run around like a madman and raise over the 400M target for Fund 1 back in 2011/2012. Fund 1's are hard to raise!!

Ultimately, we had very different styles — I liked to work with the team to write theses on where the gaps existed in different specific industries and what was possible thanks to new waves of innovation. And my part of the team was required to host hundreds of events, multiple dinners per week, in order to really map out the key founders and builders and people where we wanted to get to know them and the talent around them and find ways to be helpful to them, in order to be in the right networks and access the best investments. It's not enough just to be a successful entrepreneur, you have to really work like an entrepreneur to compete at this game, and be very strategic — or at least that's my way of doing it. My part of the team also just looked at a lot more / did more deals, which was starting to become political in fund 2 including a few things I wanted to do which got veto'd for silly reasons (I still have an email from a former partner explaining to me that I was being conned on an investment at 80-pre, and insisting that we not do it as my pace was too high vs others - and that one later sold for over $10 billion, oops). When I saw the politics, I knew we had to split it up.

My colleague Drew, now a senior partner at 8VC, also helped me between the Formation 8 funds co-found Affinity with Ray and Shubham, who have grown into truly amazing leaders — we built it for ourselves as an AI CRM with all sorts of networks and tools, and now over 3000 other firms use it. We had a different way of doing things on my team at Formation 8 and liked our deals better, so my team along with the back office — 15 of the 25 people — came over to form 8VC with me as our third fund, rather than Formation 8 Fund 3. It's hard to say I would have done things differently, because if you haven't been an investor full time and haven't worked with people at it, it's really hard to know ahead of time how to best structure things for your style and to play to your strengths and advantages, and how to keep things aligned with less politics.

We did solid work at Formation 8, and it laid the foundation for several very successful funds at 8VC and the amazing momentum we have here now with over 60 people and a team I am very proud to get to work with.

(PFE): In 2015 you started 8VC alongside some great guys and long time supporters of PFE, Jake Medwell and Drew Oetting. What are some core tenants [tenets] of 8VC that you believe founders should be aware of when looking for the best venture capitalists for their next fundraise?

(JL): Well, perhaps my biggest pitch to founders is that we’re founders ourselves, and we are still in the game, having started multiple unicorns in the past several years, and we are still going hard. I'd usually choose a successful founder from 20 years ago over a non-founder as a board member or investor, but a successful founder who has built more recently is even better - they also know what it's like to be in the trenches today. We are building things that create unfair advantages for us and our founders today, which is very different than even how things worked when I built Palantir... it's rare to have top player-coaches. When we spend time on something, it's a huge opportunity cost — we know what it's like to be a founder, and we don't want to waste your time, and we are able to help and to see patterns, and to navigate talent and BD situations and fundraising strategy. I think we've helped raise well over $20 billion into our portfolio companies at this point, after investing.

Another huge advantage we have is that we go extremely deep on a lot of large industries — we have close friends, advisors, and former colleagues who are many of the relevant leaders in logistics, healthcare, finance, government, various parts of the biology and bio-infrastructure world, defense, etc. We have built and invested in tens of hugely successful companies at this point, and constantly host events and spend time with relevant leaders, whether it's hosting a logistics summit with the most relevant and entrepreneurial leaders in the sector around the US at our vineyard estate or otherwise — and once you've done that several times, and these leaders have worked with a lot of your companies and you've built up credibility and had wins together, you can really fast-track legit things. Our brand isn't mostly a public brand, it's a brand of being the very best at what we do and knowledgeable about their industry and their needs with thousands, maybe tens of thousands of these relevant business leaders.

And it's rare to have our track record of success and credibility, with a team that is still very young and energetic and planning ahead and building alongside you for the next couple decades. Each success is a platform to be able to build more / to be able to slightly more easily have more success in the future, is the way it works.

(PFE): You are now a strong fixture in the Austin, Texas community, after moving the 8VC headquarters there in 2020. By my estimation you guys now have the largest venture fund in Austin by a significant margin. What have been the most compelling parts of Texas for you and your team to continue to be successful venture capitalists that you were unable to find in the Bay Area?

(JL): Haha! Well, my team tells me that 8VC is the biggest venture fund in Texas, although there are a surprising amount of people who are a lot wealthier than all of us all around Texas, so we shouldn't let our heads get too big for our hats. An increasing amount of our portfolio is out of Austin, including some of our 8VC Build companies I'm very excited about.

I wouldn’t say it’s about what we couldn’t find in the Bay Area – the SFBA is a great place with amazing resources, and still the world capital of engineering talent - although perhaps not as fully dominant as it once was. But the pandemic accelerated some underlying trends and taught people that maybe that dominance doesn’t need to be a complete stranglehold, and for many of our 8VC employees and our portfolio companies' employees, as well as people working on other projects of mine, the value proposition of being in Austin is a lot better than the Bay Area. By the time I moved there, I think there were already almost 1000 employees of several of our companies based in Austin — it's the center for tech in Texas. And as our portfolio companies spread around the country — we are still about 90% US — we noticed that we had companies in not just Texas but Tennessee, Florida, New York, New Hampshire, Utah, even Oklahoma and Iowa, etc. It's not unusual to be needed in DC, Boston, NYC, Florida, Minneapolis, or elsewhere for key 8VC meetings. So Texas is a relatively central location for me to get to places I need to be, and get back to my family faster.

Unfortunately, California is likely in a downward cycle. It’s still a wonderful place, but some of the major problems like housing, crime, infrastructure, are captured by government-funded special interests, which will make them very hard to fix. NGO's and government unions get paid directly billions of dollars by the CA government or its employees which run political machines which support the unaccountable bureaucracies that are unable to fix these problems and unwilling to consider other frameworks (such as accountability - for obvious reasons.) A lot of leaders and friends I know in the technology world have started to explore alternatives like Austin, Montana, Idaho, Arizona, Utah, Colorado, etc. That’s healthy and ultimately I think competition should help California get back on track in the longer-term - but first it needs the average voter to wake up to the massive scams / waste / incompetence and the fact that there are frameworks of accountability-driven innovation which could actually solve the problem, but that these powerful groups that control the legislature by the purse strings don't want to allow.

As for Austin… Austin already had a very strong foundation. Dell was built here, Trilogy was created here, UT is a massive institution with lots of great talent, and it’s the capital of the second-largest state in the country. It has a really fun culture of food and music and unique people, which I appreciate - frankly, it's a good idea to live nearby hippies for these sorts of cultural things (you just don't want them in full control of city council). There are people you have never heard of worth billions of dollars in Austin doing inspiring things there, and the energy of new people coming and building stuff, culturally and economically, is awesome. The last few years have been very inspiring and we've made great friends, and gotten to see other friends we weren't as close to before. Elon is moving a lot of people to town, and the Tesla Gigafactory is up and running. The 8VC office looking right out on South Congress is up and running — it's a beautiful building, Jake et al did a great job (he is an investing partner and builder of course, but we also put him in charge of the office because our SF office won all these awards thanks to his work. He tells us he has better taste than the rest of us. Despite the fact that I gave him aligned incentives, he still spent way too much! But it's a great location — come visit!).

People want to be here. People love to visit. And it’s reaching a critical growth threshold — like any city we have to get the leadership and infrastructure right, but I'm very bullish on Austin. Of course, I am bullish on Texas as a whole, and on America too — hence the name of my podcast www.AmericanOptimist.com.

This was an excellent interview. I already knew a lot of it as a fan of Joe, but the lessons of his time at Clarium is fascinating and new to me. Also love his sense of humor that comes across here (admitting that his humility is only relative, ha)! My only critique of Joe is his lack of self-awareness when he criticizes “insular networks” and “old boys clubs” and yet he only meets potential founders via “warm intros.”

You’d think Y Combinator would have taught VCs by now that founders should just be able to apply for funding via a standardized publicly available form (or just be able to email VCs directly), but it looks like some elements of the old boys club die hard.